Once a Potter, Always a Potter

Jim Melchert

Ninth Annual Dorothy Wilson Perkins Lecture Schein International Museum of Ceramic Art at Alfred University

November 01, 2007

Jim Melchert is primarily known for his work in clay in ways that reveal his ties to Conceptual Art. As a student of Peter Voulkos' at Berkeley in the early 1960s, he helped lay the tracks for the California Clay Movement that continues to be robust and growing.

He joined the sculpture faculty at UC-Berkeley in 1964. During leaves of absence he served as Director of the Visual Arts Program at the National Endowment for the Arts from 1977 to 1981 and as Director of the American Academy in Rome from 1984 to 1988.

Throughout his long career his work has had exposure at such venues as the Whitney Museum of Art, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Tate Liverpool, the Museums of Modern Art in Kyoto and Tokyo, at Documenta 5, and at major museums in San Francisco and Los Angeles.

If we reflect on the ways in which ceramic sculpture has evolved in the past forty or fifty years, patterns emerge in how artists have related to accepted practice. For all that may be rejected in the process of pursuing new directions, some concepts are too basic to abandon.

A number of years ago I was in Korea and saw the 3rd World Ceramics Biennale. The exhibitions were numerous and dazzling. The most interesting to me was the entitled “Trans-Ceramic-Art” in which work by sculptors who had formerly done pottery was shown alongside that of sculptors who had never thrown pots. There were differences in how they conceive of form. I can’t say that the work of either group was more significant or more compelling than the other. It is just that those with experience in pottery had resources at their disposal that continue to inform their work.

I took my first class with Pete Voulkos the summer of ’58 in Missoula. Before we could make anything we had to master throwing an 18” tall cylinder. I assumed that the point of that was to get the feel of it for our hands only to realize years later that we learned considerably more than how to reach that height. There are many things about a cylinder that throwing enables you understand. It helps if you approach it with what Suzuki-Roshi, a Zen master in the Bay Area, called a “beginner’s mind”. Approaching your life with a “beginner’s mind” will lead to discoveries you would never have imagined. Now, for instance, (picking up a cardboard mailing tube) if you look through a cylinder from one end as I am doing, it becomes a framing device. If I look at any of you through it, I can separate you from the rest of the audience. It is the same as if I were looking at you through the lens of a camera.

You might sit down sometime and hold the tube up to your ear and just listen. It is even more remarkable to hold a tube on each ear. The longer you sit, the more you will discover the nature of what is around you.

Another extraordinary thing about a cylinder is its strength. Stand it on end and it will support your weight, but if you lay it on its side you could crush it. To be strong one way and weak in another are interesting contradictions. Stood on end, the tube is stable and won’t go anywhere. On its side it might roll out from under you.

I can cap it at one end. A cap, of course, is what you put on your head. Stick one on the top end of the cylinder and it becomes a drumhead. It’s curious that when we make a clay cylinder we have the head at the bottom, like a wellspring. In that way you make a container, which implies that it can be filled. Yet it doesn’t have to contain anything to be full of something. The hollow has a life of its own to be enjoyed as it is.

You can see that the end of the mailing tube is a perfect circle. Yet when I set the tube down and look at it from an angle, what I see isn’t a circle. It has become an ellipse. You can watch the ellipse change shape by walking around it. What you see depends as much on you as it does on what you’re looking at. That applies to most of the things we encounter.

Those of you in the audience who are sitting close to the stage will see that this mailing tube was constructed in a spiral. Spiraling is what we associate with growing plants, the twining of vines as well as the branches that emerge from them. The spiral is also the form that clay takes when it is being thrown on the wheel. Once you open the centered mound, it will spiral out to where you will begin the wall. Pressure will make it rise and spiral into a cylinder. At the same time you will also have created an axis inside it. You only see the one but you get them both.

When I came back from the Biennale in Korea I thought about what some sculptors owe to their having started out by making vessels. I would like to show you what I’ve begun seeing in their work.

John Mason is an excellent example. The image on the screen is of an early outdoor work that I remember from the Pasadena Museum in about 1972. (see image behind Melchert at top of page) John had abandoned throwing, having found the wheel to be tyrannical. He first built massive clay walls and used a grid system to cut them. Later he even questioned the notion that is dear to craft that your work should show evidence of the hand. This led to his using commercial brick as a modular unit. He chose to build the structure with kiln brick. Years before he had dispensed with utility as a function of pottery. Now he was rejecting utility as a function for kiln brick. But consider how he held on to the circle and the vertical axis that he knew as a potter. He bisected the circle and had them interlock at their centers.

(see image #2) In more recent years he turned from brick to large slabs of clay. He continues to rely on a vertical axis along which the blades are positioned in a spiral. (see image #3) What John Mason’s work shows us is that you don’t necessarily throw the baby out with the bath water when you leave pottery for sculpture-making.

Now I am going to make a big leap. In contrast to the austerity of John Mason’s classic sculptures, let us consider a very different sensibility by taking a brief look at a work of Howard Kottler’s. I have chosen his vessel in the shape of the lower case letter “i”. (see image #4) He has doubled the dots, no doubt a gender reference, and has attached flanges that indulge a taste for flamboyance. His colors are a triad of intense primaries, red, yellow, and blue. The piece can be read as a declaration of personal identity, the “I” of who I am. The work is prescient in that it anticipates much of what has since occurred, not only in regard to the aesthetic canon, but in the social politics of recent years.

Adrian Saxe is a master at making the most of the attachments. He likes to exploit the incongruity of the components that make up a teapot. No one does it better. (see image #5)

Adrian’s phenomenal sales didn’t escape Mark Burns’ notice. Mark was a student of Howard Kottler’s and like him, initiated new directions. In this case it is the drawing of the salesman that alludes to the newspaper ads of a used car dealer. (see image #6) Commercial cartooning was not a source of ideas for my generation, but by now the stuff of advertising has become a magnet for many a young artist.

A teapot of Jeremy Hatch’s proposes that this icon could take the form of a kit. The work is in porcelain and made of detachable parts that can be unscrewed and reassembled. (see image #7)

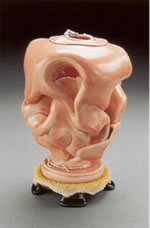

The soft melting surface of this ware by Kathy Butterly winks at George Ohr. (see image #8) It has the look of a nearly deflated balloon, leaving the piece with more surface than its size would suggest. The preciousness of the attachments stretch its humor even further.

All this is to show that there are multiple ways in which artists have explored forms that draw on those basic to pottery.

Leopold Foulem sets up an engaging conundrum by depriving an iconic vessel of its opening. It is a vessel that is not a vessel. (see image #9)

The live void inside one has long interested Toshiko Takaezu. She has found a way to alter our perception of its volume by reducing the size of the entrance to it. For her the hole is also the critical point where the interior and the exterior meet and become the other. (see image #10)

The opening in a Ken Price ware never looks arbitrary or passive. It can give an amorphous shape an interior and an orientation. (see image #11)

Tony Marsh uses a field of perforations to lighten the mass and obscure the form of what would otherwise be solid objects. The field almost sets up a vibration in the way that filigree pattern does. (see image #12)

By contrast we have Pete Voulkos’ iconic “Rocking Pot” from 1958. (see image #13) You sense the determination of the knife slicing through the clay to liberate the interior, to liberate Pete himself from prevailing notions of what constituted a pot.

I’ve see two or three of Eva Hild’s sculptures in which the openings lead to interweaving caverns. (see image #14)

In English we have only one word for a hole. In Italian there are two. A buco goes all the way through, like a button hole. A buca doesn’t, such a hole in the ground or an oven. (see image #15) Richard DeVore liked to use both and play one off the other. By inserting a false bottom, he would have you perceive the outside and the inside differently. (see image #16) An opening in the pit sometimes exposes more than one lower cavity.

Peter Beasecker has also worked with the notion of the ambiguous chamber and hollows within walls. (see image #17) Like John Mason he has a good feel for geometry. This basket-like tray of cups also plays with walls within walls.

I want to talk about kilns next and ways in which artists have extended our concept of their interiors and the openings into them. But before we do, let’s take one last look at the spiral which has been central to this discussion. Mary Roettger is an alumna of Alfred who lives in Minnesota. She has been making sculptures like this big coil that can be seen through its axis or (see image #18) from its side, either way it is the essential metaphor for the thrown clay cylinder.

Gifford Myers has done much of his ceramic work in and around Faenza on the northwestern coast of Italy. Gifford once wrote that he was intrigued by the process of ceramics as a genre dependent on technical know-how. He has remarked that the process of firing is often more fascinating than what comes out of it. “The Furthest Way About Is the Nearest Way Home” is a 40” long clay tube glazed at one end. (see image #19) The work began when he improvised a simple kiln with a can, a tank of gas, and a burner. He inserted the glazed end of the tube into the can through a hole on its side so that half of it was completely fired. The tube is now presented as a wall sculpture, but it is really evidence of how it was made. The half that was outside the “kiln” registers the progression of the heat from one end to the other. It is entirely linear work.

Potters who take turns firing wood kilns know what an event it is, but what matters most are the wares inside. Already as a student John Roloff thought otherwise. For him the essential part of the process was the firing. By the late ‘70s he began constructing outdoor kilns that would simply fire themselves. (see image #20) The work on the screen is “Untitled/Earth Orchid” and was done in 1982. It is 20’ high, 34’ long, and 4’ deep. The walls are made of cast refractory cement, reinforced by steel, and insulated with a temporary ceramic fiber. It burned natural gas. The center is where the heat first built up. The glow proceeded down the two channels towards the stacks. (see image #21)

John is quoted as saying that visually “the process suggested the idea of transformation or growth, as if sap were flowing through it, making it alive.” (See footnote) John recalls that the sound of the burners suggested that the kiln was alive. (see image #22) You can see how much was changed by the fire. Since the stacks were left in place as part of the evidence.

The final work I want to show you is by John Balestreri. He once built a wood burning kiln by tunneling into the hillside on his parents’ land near Boulder. It had to have taken a lot of work. Once it was done he chose to honor the cavity by using it as a press mould. He packed the walls with clay connected to a core that could be removed after the firing. (see image #23) He then exhibited it section by section like a great sliced creature. What he had done was transform a negative space into its positive counterpart. Such an act has ties with the “beginner’s mind” that Suzuki-Roshi would have us cultivate.

Footnote: The quote is from an interview with John done by Nan Hall in May 1990.

#2 John Mason

#3 John Mason

#4 Howard Kottler

#5 Adrian Saxe

#6 Mark Burns

#7 Jeremy Hatch

#8 Kathy Butterly

#9 Leopold Foulem

#10 Toshiko Takaezu

#11 Ken Price

#12 Tony Marsh

#13 Peter Voulkos

#14 Eva Hild

#15 Richard Devore

#16 Richard Devore

#17 Peter Beasecker

#18 Mary Roettger

#19 Gifford Myers

#20 John Roloff

#21 John Roloff

#22 John Roloff

#23 John Balestreri